The year 2024 will be remembered as a period of profound contradictions in the history of Mexican bullfighting. While the country was moving toward a new constitutional paradigm that recognizes animals as sentient beings worthy of protection, 418 bullfighting events — including bullfights, novilladas, and calf fights — were held across different states of the country. This figure, documented by research conducted by Sofía Morín, a lawyer specializing in animal law, reveals the persistence of an industry that refuses to disappear despite growing social rejection and a legal framework that is increasingly closing in on it.

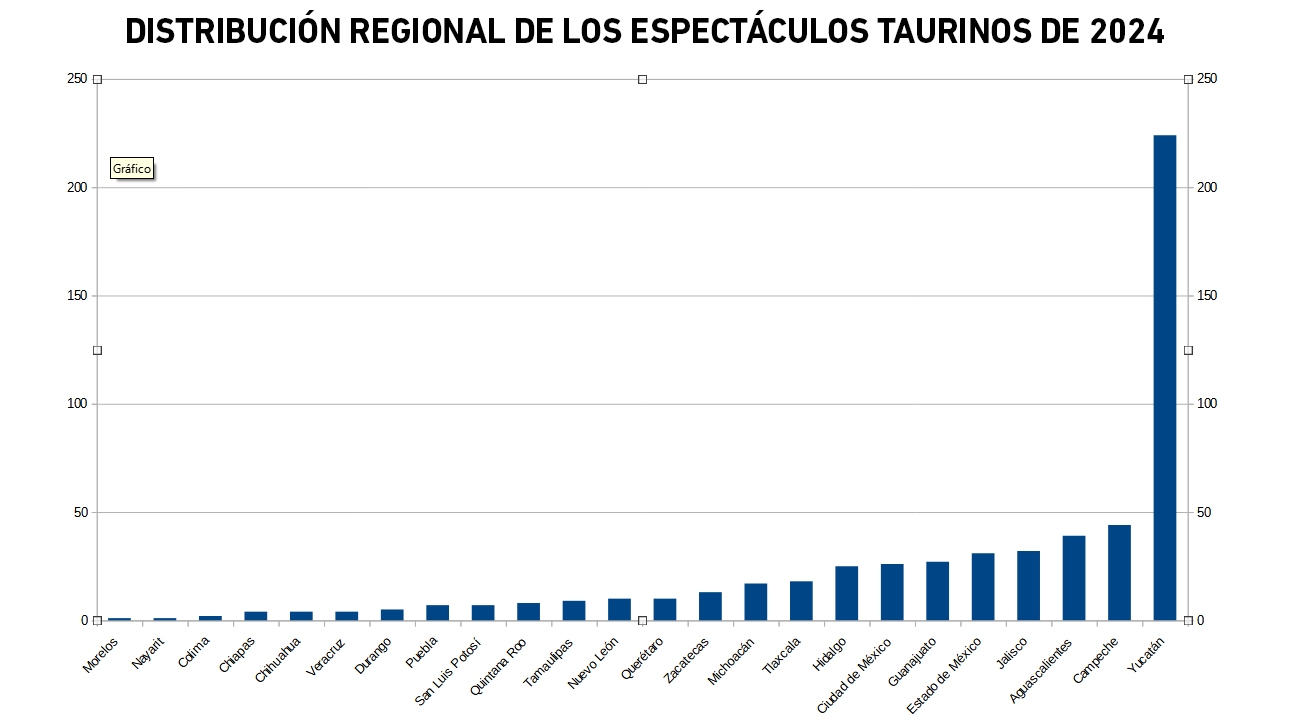

"The data from 2024 show that bullfighting is not a deeply rooted tradition throughout Mexico, but rather an imposition concentrated in certain states and sustained by specific economic and political interests", explains Morín. "When we analyze the figures, we see that three states — Yucatán, Campeche, and Aguascalientes — account for more than 37% of all events nationwide. This debunks the argument that it is a widespread cultural practice".

An unequal geography of violence

The territorial distribution of bullfighting events in 2024 confirms that the so-called fiesta brava is not a uniform phenomenon in Mexico. Yucatán topped the list with 73 events, followed by Campeche with 44 and Aguascalientes with 39. This geographic concentration stands in stark contrast to states such as Sonora, Coahuila, Guerrero, Quintana Roo, and Sinaloa, where bullfighting has been completely banned since before 2024.

"The concentration of events in certain states reveals how this industry operates", Morín adds. "We are not talking about a spontaneous cultural expression, but about a business controlled by specific ranches and promoters who enjoy political protection. The 418 events do not represent the will of millions of Mexicans, but rather the interests of an economic elite that exploits animals for profit".

A particularly alarming fact is that in Quintana Roo, where bullfighting is legally prohibited, 8 illegal bullfighting events were recorded in 2024. This disregard for state law highlights the impunity with which the sector operates and the lack of effective oversight and sanctioning mechanisms on the part of the authorities.

A spectacle of men, for men

An analysis of who participates in these events reveals another dimension of the problem: Mexican bullfighting is overwhelmingly male-dominated. Of the 323 bullfighters who performed in 2024, only 9 were women, representing just 2.8% of the total. This statistic dismantles any argument about diversity or inclusion within the sector.

"The deeply macho nature of bullfighting is no accident", says Morín. "It is a spectacle that glorifies a form of masculinity based on violent domination, where ‘bravery’ is measured by the ability to torture and kill a defenseless animal. The fact that 97% of bullfighters are men is not a coincidence; it is part of a patriarchal structure that equates manhood with violence".

The research also revealed that there were more novice bullfighters (146) than matadors (126), as well as 23 mounted bullfighters, 15 amateur participants, and 13 calf fighters. Of all bullfighters, 130 individuals — more than 40% — performed only once throughout the entire year, calling into question the claim that bullfighting represents a stable source of employment.

Livestock monopoly and economic concentration

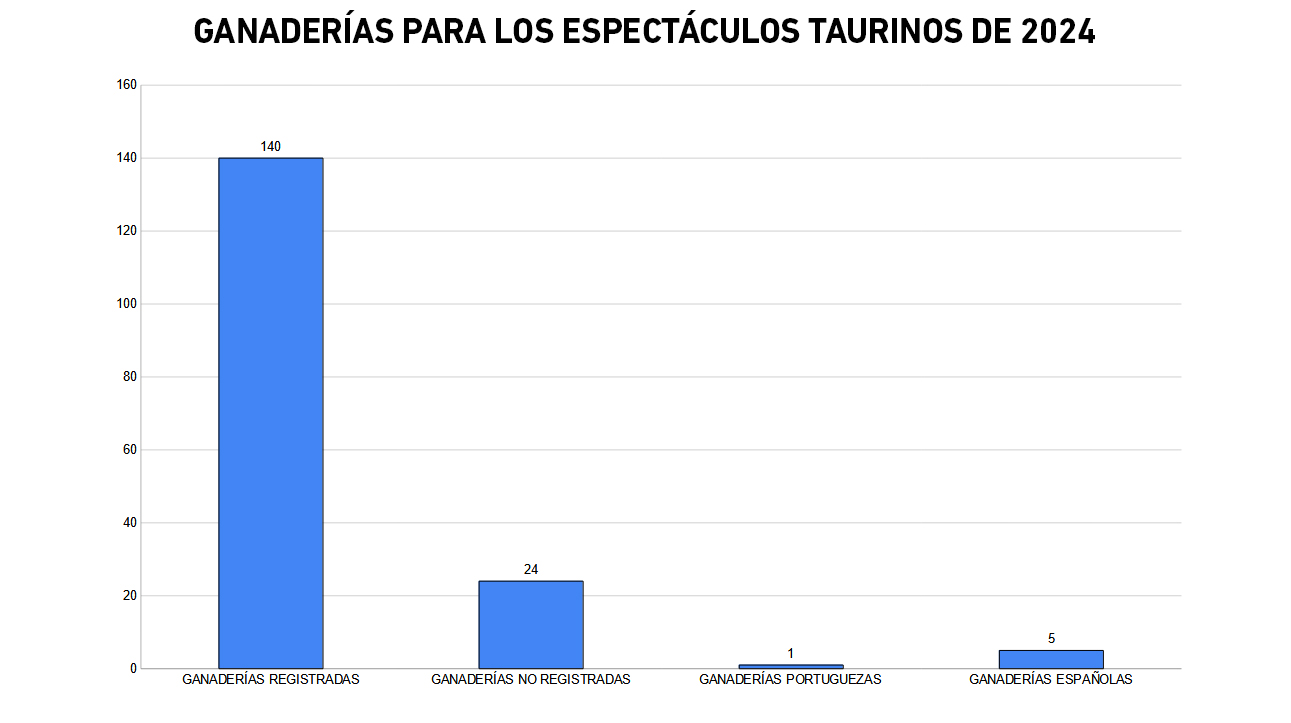

An analysis of the breeding sector reveals that Mexican bullfighting is dominated by a handful of breeders. Of the 245 fighting bull ranches registered with the National Association of Fighting Bull Breeders (ANCTL), only 140 sold animals for bullfighting events in 2024. Even more telling: of the 170 ranches that commercialized bulls, 65 — that is, 38% — participated in only a single bullfight throughout the entire year.

Four ranches control the market: San Marcos (Jalisco) with 18 bullfights, San Martín de Porres (Yucatán, unregistered) with 17, Quiriceo (Campeche) with 15, and Marrón (Guanajuato) also with 15. These four operations accounted for 15.5% of all events nationwide.

"Calling bullfighting ‘cultural heritage’ is a fallacy when it is controlled by four ranches and a handful of businessmen", Morín argues. "This is not popular culture; it is an oligopoly that generates millions of pesos at the expense of animal suffering and protects itself through networks of political corruption. The figures show that we are dealing with a private business, not a tradition of the Mexican people".

The employment myth and the seasonal nature of the business

One of the most commonly used arguments by the bullfighting industry to resist bans is the alleged loss of jobs. However, the 2024 data contradict this narrative. With 323 bullfighters across 418 events, each participant averaged just 3.9 performances throughout the year. This means that even for those working directly in the ring, bullfighting does not represent a steady source of income but rather an occasional activity.

"The employment argument is profoundly dishonest", explains Morín. "First, because the numbers show it is a seasonal activity that does not generate permanent jobs for most participants. Second, because no alleged economic benefit can justify the systematic torture of thousands of animals. And third, because transitioning toward non-violent spectacles or other cultural and tourism industries can generate dignified and ethical jobs — something bullfighting will never achieve".

The concentration of events on specific dates — state fairs and patron saint festivities — confirms that this is a seasonal activity tied to government contracts and public subsidies, not an industry that generates year-round employment.

2024: the year of constitutional reform

On December 2, 2024, Mexico took a historic step with the publication in the Official Gazette of the Federation of a constitutional reform amending Articles 3, 4, and 73 of the Constitution. The addition to Article 4 explicitly establishes that "animal abuse is prohibited", elevating animal welfare to constitutional status and obligating the State to guarantee their protection.

This reform represents the most forceful legal blow bullfighting has ever received in the country’s history. By turning animal abuse into a constitutional violation, any attempt to justify the torture of bulls on the grounds of tradition or culture is effectively eliminated.

"The constitutional reform of December 2024 changed the entire legal landscape", says Morín. "From that moment on, every bullfight held in Mexico is, technically, a violation of the Constitution. The problem is that power structures continue to protect the bullfighting industry through judicial delays, administrative omissions, and political complicity. But the law is clear: bullfighting is animal abuse and therefore unconstitutional".

States that move forward, states that resist

Throughout 2024 and early 2025, several Mexican states consolidated or implemented total bans on bullfighting. Sonora has maintained its pioneering stance since 2013, while Michoacán joined this group on April 3, 2025, following a historic vote in its local Congress banning any spectacle involving bloodshed or animal suffering.

Mexico City adopted a controversial hybrid model: in March 2025 it implemented the concept of a “violence-free bullfighting spectacle”, which prohibits killing the animal, bans the use of sharp instruments, and limits encounters to 10 minutes per bull. While intended as a compromise, in practice it amounts to a de facto ban, as it removes the core elements of traditional bullfighting.

"State-level bans are important advances, but they are insufficient as long as there is no federal law prohibiting bullfighting throughout the national territory", says Arturo Berlanga, director of AnimaNaturalis in Mexico. "Legislative fragmentation allows bullfighting promoters to seek refuge in states with lax regulations or corrupt authorities. Mexico needs a General Animal Welfare Law that establishes uniform minimum protection standards across the country".

Sanitary illegality: an unexplored path

One of the most significant findings of the legal analysis conducted by AnimaNaturalis and CAS International is that bullfighting systematically violates the Federal Animal Health Law and NOM-033-SAG-ZOO-2014, which regulates methods for killing animals.

These regulations establish that the killing of animals not intended for human consumption is only permitted in cases of disease, accident, or incurable suffering, and must be carried out using procedures that minimize pain. Bullfighting — with its lances, banderillas, swords, and daggers — is the antithesis of humane slaughter.

In May 2024, a federal court ordered the SADER (Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development) and SENASICA (National Service for Agri-Food Health, Safety, and Quality) to inspect and sanction bullfights for violating these regulations. Fines can range from 2.4 to 12.4 million pesos per event.

"The sanitary route is extremely effective because it does not require complex legislative changes", explains Berlanga. "The laws already exist and are clear. The problem is that federal authorities have systematically failed to enforce them, likely due to political pressure from bullfighting businessmen. But we now have a court ruling ordering them to act. If SENASICA fulfilled its legal obligation, bullfighting would become economically unviable within a matter of months".

Corruption as the backbone of the system

The persistence of bullfighting despite widespread social rejection and the new constitutional framework is largely explained by corruption networks linking bullfighting businessmen to high-level political figures.

The most emblematic case is that of federal congressman Pedro Haces Barba (Morena), owner of a bullring in Ajusco, founder of the Mexican Association of Bullfighting, and leader of CATEM. According to the “2025 Corruption Yearbook” published by Mexicans Against Corruption and Impunity (MCCI), Haces has used his legislative position to block anti-bullfighting reforms and financially benefit his inner circle.

The Baillères and Cosío families, owners of Plaza México and influential ranches, represent the economic power shielding the sector. These groups have engaged in intense lobbying to delay judicial proceedings at the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation (SCJN), which has repeatedly refused to take up injunctions that could definitively resolve the constitutionality of bullfighting.

"Corruption is the invisible pillar sustaining bullfighting in Mexico", denounces Berlanga. "Without the complicity of lawmakers like Haces, without the inaction of sanitary authorities, without the lobbying of economic elites that control the bullrings, this violent spectacle would have already disappeared. The 418 events of 2024 are not proof of cultural roots; they are proof of systemic impunity".

A spectacle alien to Mexican culture

Contrary to what bullfighting propaganda claims, bullfighting is not part of Mexico’s original culture but a Spanish colonial imposition. Indigenous and mestizo communities in the country developed ways of relating to animals based on respect and reciprocity, not on torture as entertainment.

"It is essential to dismantle the myth that bullfighting is ‘Mexican’", emphasizes Morín. "It is a colonial legacy that never represented the majority of the population. True Mexican traditions are found in our community festivals, our gastronomy, our art, and our music. Bullfighting is an imposition by elites that has been maintained through economic and political privileges, not through genuine popular roots".

Recent surveys show that more than 70% of the Mexican population rejects bullfighting, with opposition even stronger among younger generations. This confirms that Mexican society is moving toward an ethic of respect for animals that is incompatible with bullfighting violence.

Harm to childhood and the pedagogy of violence

One of the most troubling aspects of bullfighting is its impact on the emotional development of children and adolescents. Since 2015, the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child has recommended that Mexico prohibit minors from participating in bullfighting schools and attending bullfights as spectators, arguing that exposure to this type of violence has harmful effects on their physical, mental, and moral development.

Psychological studies cited by organizations such as CoPPA (Collective of Professionals for the Prevention of Animal Cruelty) and the Franz Weber Foundation indicate that normalizing animal abuse in festive contexts can be a precursor to violent behavior in other areas. Desensitization to the suffering of others, particularly when celebrated by authority figures, distorts children’s capacity for empathy.

"In a country with alarming levels of interpersonal violence like Mexico, allowing children to witness and celebrate the torture of an animal is pedagogically irresponsible and socially dangerous", warns Berlanga. "We cannot aspire to build a peaceful society if we continue teaching our children that violence can be entertainment. Banning bullfighting is also a long-term violence prevention measure".

The path toward definitive abolition

The data from 2024 confirm that Mexican bullfighting has reached a point of no return. The industry has lost the ethical, legal, and social battle. The constitutional reform of December 2024, the expanding state-level bans, court rulings ordering the enforcement of sanitary regulations, and the majority rejection by the population create a scenario in which the sector’s survival depends solely on corruption and impunity.

"The 418 events of 2024 are the last gasp of a dying industry", concludes Morín. "Every bullfight held today is an affront to the Constitution, to animal health laws, and to the ethics that most Mexicans have already embraced. The question is not whether bullfighting will disappear in Mexico, but when we will have the political courage to enforce the laws that already exist and permanently close the torture arenas that still operate under the protection of corruption".

The transition toward a Mexico free from bullfighting violence is not a future aspiration but a legal reality in the process of consolidation. The data from 2024 do not show a vibrant tradition, but rather a residual industry artificially sustained by illegitimate privileges that the State is beginning to dismantle. The end of bullfighting in Mexico is inevitable; all that remains is the political will to carry it out.